Cycling the Pamir Highway in Tajikistan was a dream of mine since 2015, when I read about the first stories from other travelers who cycled the Pamir Highway and as I decided that I’m going to do a world trip by bicycle. Now, 4 years later, I was right before crossing to Tajikistan and finally cycling and experiencing the adventurous Pamir Highway on my own.

After a few days of rest and historical culture in Samarkand, we left the city on the morning of the 5th October 2019 as a group of four. Andrew already had to leave us in Bukhara as his Tajikistan Visa so as GBAO-Permit was about to start and also end earlier than ours. So we have agreed that we will hopefully meet again in Dushanbe about a week later. As we left Samarkand, we could already see the first mountains on the horizon, which felt great and super exciting after all these weeks through deserts and flatlands. The border to Tajikistan was only a 40km ride away. Around midday, after the last stop for some more delicious Uzbek Somsa’s, we reached the border checkpoint.

What we expected was a long, time-consuming inspection on the Tadjik side, but it was nothing like that. First, on the Uzbek side of the border, we changed our last few Som’s for Tadjik Somoni to a rather bad exchange rate and bought a few more Snickers for the road. Then the Uzbek border police stamped us out and we were able to directly cross into Tajikistan without any waiting. On the Tadjik side, there was a small customs container where we had to show and stamp our Visas and a few minutes later it was all done.

The first few kilometers in Tajikistan felt great. There was this adventurous feeling in the air, the anticipation for cycling the Pamir Highway, and the upcoming climbs and adventures. As soon as we crossed the border, the mountains started to rise on both sides of the road.

Tajikistan, a country where more than 90% of its territory is mountainous and half of it lies 3000m or more above sea level, is an absolute dream for every adventurer and especially, landscape photographer. I couldn’t wait to see more of it!

The mountains haven’t been the only thing that changed after the border crossing. In every little village we cycled through, there were dozens of kids shouting “HELLLOOOOO” and running towards us to get a high-five as soon as they saw us. This was also something I previously heard and read about from other cyclists who have been in Tajikistan, but I couldn’t really imagine what extent it would be. There was a hello from everywhere, and not only all these hundreds of kids were happy to see us, but also the older ones were quite welcoming and friendly.

On this first day, we cycled around 40 more kilometers in Tajikistan and finally found a perfect camp spot just a few meters next to the main road, next to an empty hut with a huge and wide view over the Serafschan river and the valley below. We did not only get a magical sunset and sunrise but were also able to start the next day with a downhill instead of a climb.

The first big climb

The second day was meant to be the warm-up for the third day and the first big climb to come. After a few more kilometers through the rather open valley, more and more mountains piled up on both sides of the road, and the valley got more and more narrow. Slowly we climbed up on fairly well-paved roads, through tiny villages who looked like green oases, always having the Serafschan river next to the road. As the valley was so narrow, we couldn’t find a flat place suitable for 3 tents as it was getting dark. Just before there were only the road and the river left in the valley, we stopped at a restaurant to ask if we could put our tents somewhere outside or in the parking spaces.

They told us that the owner was not there and that they’re going to call him to ask him about our overnight-stay. 1.5 hours later the owner still hasn’t come over, so we asked the staff to call him again. After a long discussion, he finally accepted to let us stay and as it was already pretty cold, they offered us to stay in a tiny room full of small mattresses, which was used for the stuff or maybe also other guests to get some sleep. In the room of about 5 by 5 meters, we put in all our 25+ bags and fell asleep side by side.

The next day, it was time for the first big climb, 1800hm up to the Anzob-Tunnel, and after that, all down again to the capital of Dushanbe. As the day before, we slowly cycled up through narrow valleys, through some tiny villages where we bought bread and other food and still next to another river coming down from the mountain. The scenery was amazing. Near some villages, they had like small stone-houses at the river bench with a lot of horses, cows, or other animals walking around or drinking water from the river. In one village they even made kind of an outdoor fridge as they put drinks on shelves with cold spring water running down the wall and over the drinks.

From halfway up the climb, it started to get steeper. From now on I often had to go off the bike and push. With a total of 160kg, it quickly became impossible for me to cycle on steep sections. However, I have already got used to it to push the bike and I also liked the variety because you needed different muscle groups and others could recover. My rule of thumb was always the same, if I couldn’t cycle faster than 7km/h, I went off and pushed the bike as I also went 7km/h while pushing it.

At 2720m we finally reached the famous Anzob tunnel a.k.a. the “tunnel of death”. The Anzob tunnel is known to be one of the most, if not the most dangerous street tunnels in the world regarding the number of people who already died inside the tunnel. The tunnel is considered to be dangerous as it was never properly completed despite the reopening. As there is no adequate ventilation, there is a high-value carbon monoxide inside the tunnel which makes it hard to breathe and what had already cost some drivers their lives as they stuck in a traffic jam. Some other things are lack of light, some potholes, and the partially flooded road in the tunnel.

As we arrived at the Anzob tunnel, the police stopped and forbade us to cycle through the tunnel. We had to wait for an empty gravel-truck to take us and our bikes through the tunnel. To heave up all the bikes and bags up to the loading area of the truck was quite a fun matter. Favio was the last to climb into the truck bed and although he was still standing, the driver just drove off into the tunnel. It was exciting and scary at the same time to see how fast he was driving through the tunnel.

But hey, as I’m writing all this, we made it to the other side of the tunnel! Luckily we made a picture of ourselves before and after the tunnel. Our faces were super dirty from the sweat and all the soot in the tunnel.

On the other side of the tunnel, we were offered breathtaking views with lots of huge, snow-covered Pamir mountains. What followed was a long and smooth downhill, all the way from 2700m down to Dushanbe at 815m. For the last two hours, we cycled in complete darkness, always in one line and with enough distance, so we could react to potholes or the warnings from the one in front of the group.

At around 9pm we made it to Dushanbe and the greenhouse Hostel, super tired but also super happy we made it to the capital of Tajikistan.

Dushanbe

In Dushanbe, we were ready to get some well-earned sleep and a few days of rest before moving on for cycling the Pamir Highway. The greenhouse Hostel we stayed in is a real Hotspot for a lot of people travelling the Pamir Highway, especially cyclists. There we also met a familiar face again, Andrew who arrived a few days before us. There were some more cyclists too, in which some of them cycled the Pamir Highway the other way around, from Kyrgyzstan to Tajikistan and Dushanbe. Next to the cyclists, there were some more people who did the M41 by motorbike or by car.

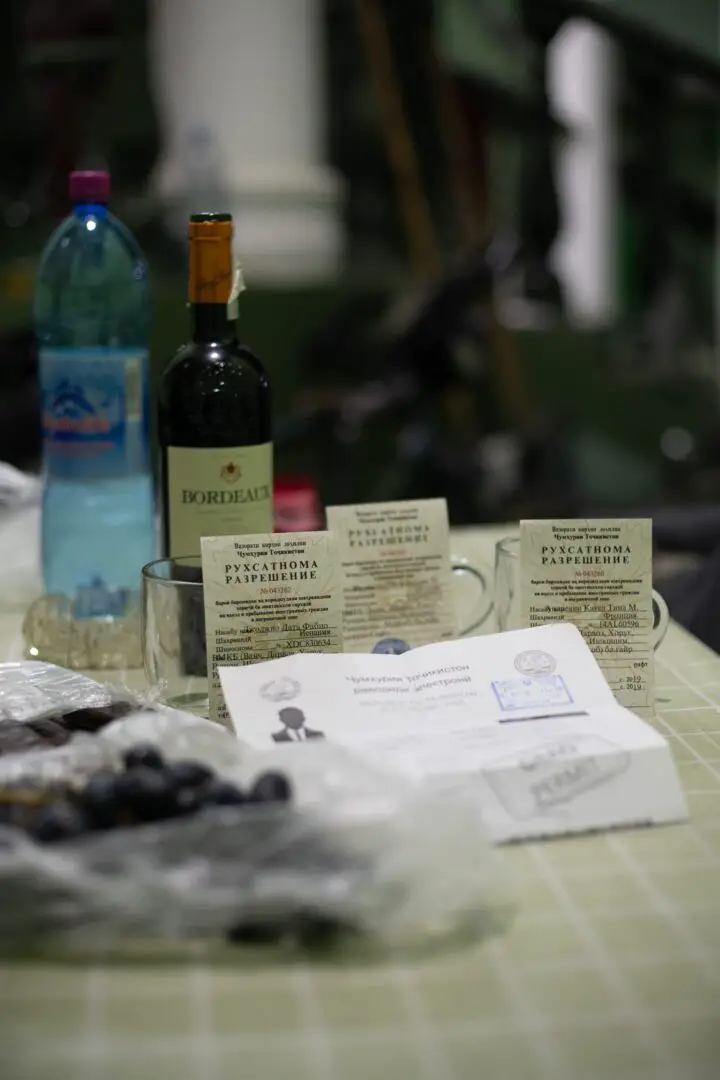

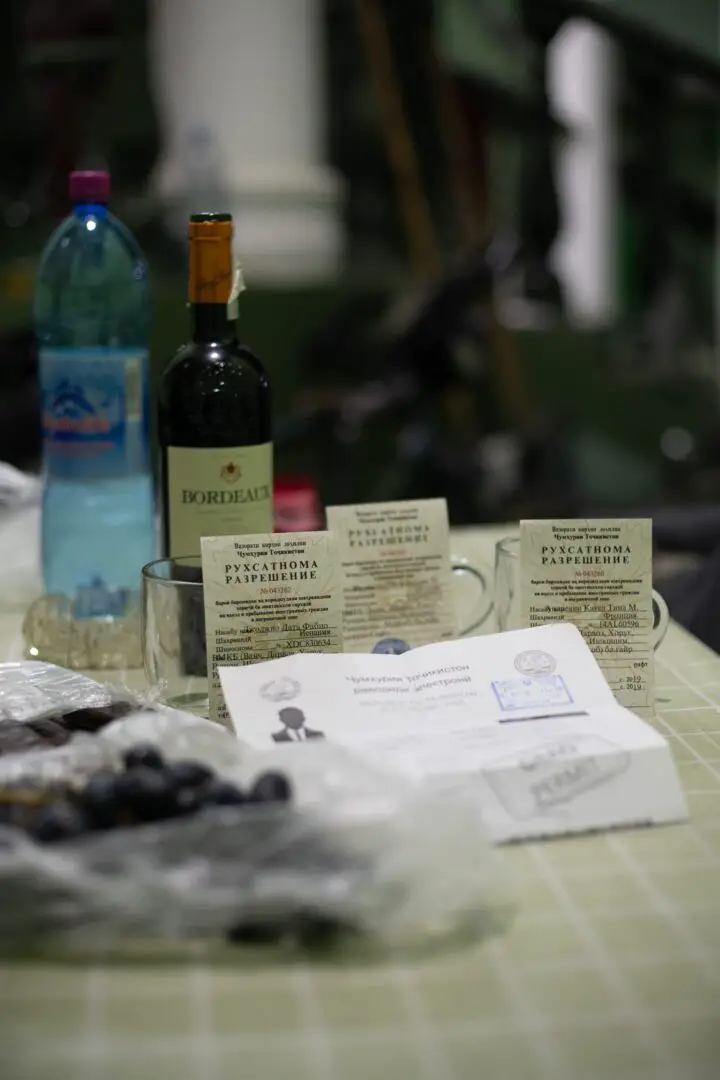

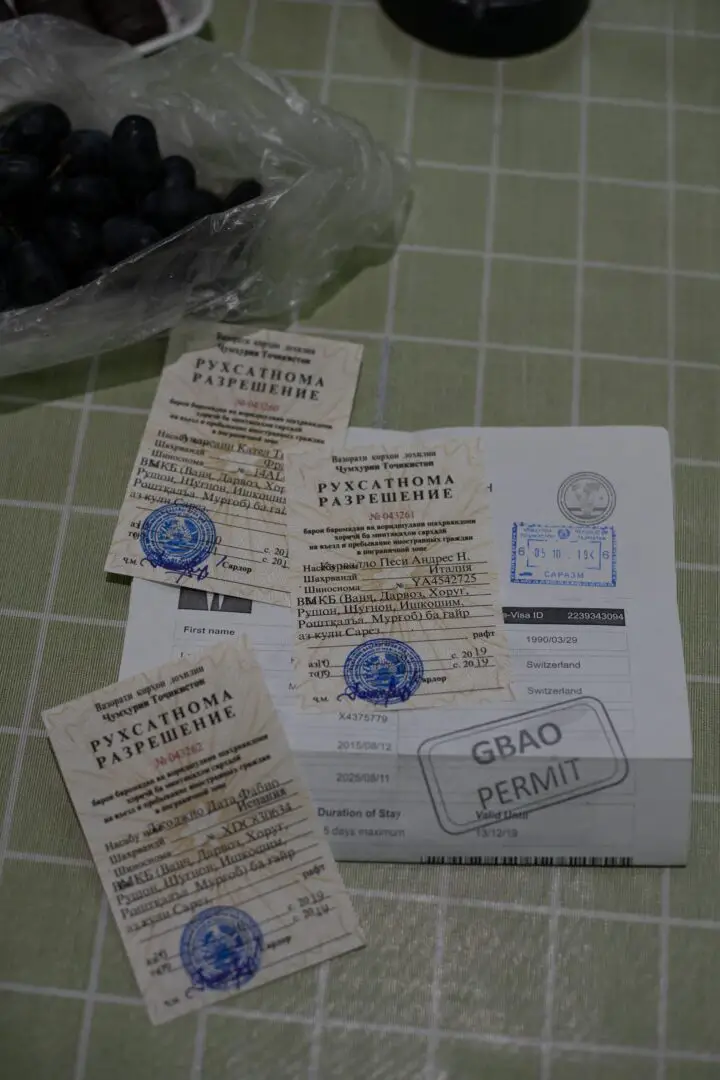

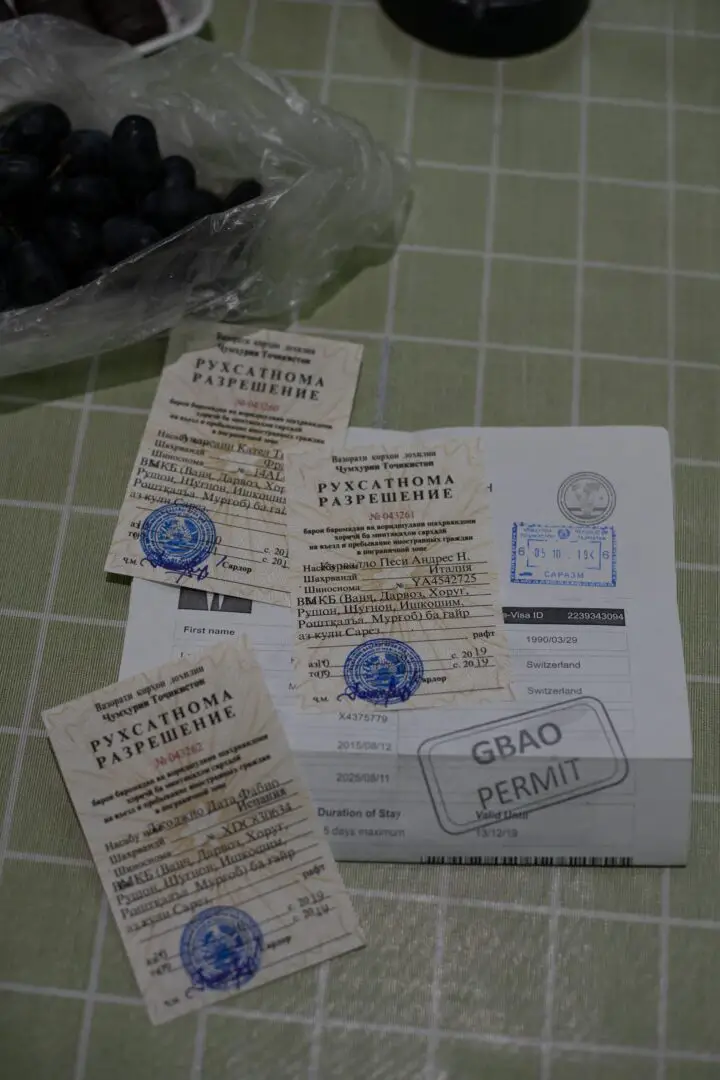

In Dushanbe, we had to organize some more things. Favio, Kata and Andres needed to get the GBAO-Permit (a special Permit to travel the region of Gorno-Badachschan around Khorog) and we also wanted to find a sim-card for Tajikistan. After a long sleep, we went to the city to organize these things and as the others had to wait at the migration police for their GBAO-Permit (I already got mine together with the e-visa), I went to the nearby hairdresser to lose some more weight for the upcoming climbs.

After that, we went to a big supermarket to get enough food, snacks and chocolate spread for the next days on the bikes. What we were also looking for was a big and thick wool blanked for Favio. As he didn’t have a sufficiently warm sleeping bag for the cold temperatures to come, I had the idea of sewing one himself instead of buying a bulky an overpriced sleeping bag from an outdoor shop in Dushanbe.

With fully loaded backpacks we returned to the hostel where we had a bottle of red wine to celebrate the previous days on the road together, as well as the upcoming Pamir adventure. After all, we had been traveling together for more than a month now. Already while cycling in the desert, we asked ourselves which of the four routes we should take through the Pamirs. Already there we came to the conclusion that we all wanted to cycle the Bartang Valley, the shortest, most remote, most scenic and toughest of the four routes.

Andrew, who cycled the previous days in Tajikistan with another cyclist and who had a much lighter bike than the four of us, decided to go for another option. His Idea was to cycle along the M41, cycling back through the Wakhan valley to Rushan and finally doing, together with us, the Bartang valley. So we said goodbye to him the next morning, while we stayed in Dushanbe for two more days.

In these two days, we had one more thing to do, probably one of the most important ones, checking and getting our bikes ready! They already had a lot of kilometers to endure, especially through all the dry, sandy desert the weeks before. Before we could leave Dushanbe, we had to be sure the bikes were in proper condition without having any major issues before cycling the Pamir Highway. The Pamir Highway is one of the main and most famous cycling hotspots on this planet, well known for the adventure and the beautiful scenery. But the highway is also known to be one of the worst ones to cycle when it comes to road conditions.

We were about to cycle on lots of hard gravel and pushing our bikes through sand, rivers, or snow. When I planned and build my custom touring bike, I’ve selected some of the sturdiest components I could get. Cycling the Pamir Highway thought was definitely going to be the test if I planned well. Dushanbe was the last city on our route in Tajikistan where we could get new parts like chains, cassettes, or breaking pads. If something like a hub, or a rim was going to break in an area like the Bartang valley, then walking had been the result.

Well rested, well equipped and full of motivation, we left Dushanbe and the greenhouse Hostel in the early morning of 11.10.2019.

M41, cycling the Pamir Highway from Dushanbe to Khalai-Khumb along the north route

A bit outside of Dushanbe we met Viktor, a Hungarian cyclist on a recumbent bike we already met at the greenhouse hostel when he came by to meet one of the bicycle mechanics. As he was going to cycle the same route until Rushan, we were happy he was going to join our group.

From Dushanbe, there are two different routes you can take up to Khalai-Khumb, when both routes join together again at the Panj river. The north route continues along the M41 for about 280km’s, which is the shorter, harder, and more scenic of the two routes with more climbing involved. The 366km long south route instead leaves the M41 20km out of Dushanbe towards the south, mostly on good tarmac past the Nurek Reservoir, through the city of Kulob and along the Panj river and the Afghan border to Khalai-Khumb.

You guess which way we took, the more adventurous one of course. Just a few minutes after we met Viktor again, Kata had to stop cycling as the rear wheel of her bike wasn’t running straight. The axle of her rear hub was loose, but with some different tools and the help of Viktor, the wheel was fixed soon.

A short time later we had to stop again, this time it was because of me. I had to take a picture of my cycling computer as I just hit my first 10’000km’s on this tour. It was an amazing feeling, realizing that I cycled all this on my own power, from Bern to Tajikistan, how surreal it was. Moreover, it was a nice coincidence as I hit these 10’000 on the first day cycling the Pamir Highway, the first day on the official M41. How long I was looking forward to that!

We took it easy that day. After 50km we found a flat, green field to camp for the night. The next day there was a bit more climbing involved. We cycled through open valleys with fantastic views over the surrounding mountains and the picturesque river valleys. It was a lot of up and down, climbing up and around a river valley and rolling down at the end of it, just before starting with the next one.

Cause of the “short” detour over Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan instead of Turkmenistan, I was here in the Pamirs 1.5 months later than planned, and the cycling season here at the Pamir Highway slowly but surely came to an end. But not only the cycling season, but also the ones of the many shepherds having their flock up in the high mountains.

We got to see Transhumance in Tajikistan, the seasonal movement of livestock. On our way up to our first high pass on the Pamir Highway, we met a lot of shepherds with their huge flock, coming down from the mountains before winter. Sometimes we had to let pass hundreds if not thousands of sheep and some heavily loaded donkeys, carrying all the luggage of the shepherds, which were themselves riding a horse and marking the end of the parade.

At the end of this day, we found another flat and green field just next to kind of a water reservoir of the kysylsuu river. In general, wild camping in Tajikistan and along the Pamir Highway, and although we are in high mountains, is super easy. There are a lot of flat, green and grassy places, most of them nicely cut be hundreds of sheep. The only thing you hear is the trucks that drive till late in the night on the M41 or noise from the rivers. Except that, nights are super quiet and you open the tent in the morning, starting the new day with staring at these beautiful and majestic mountains which surround you.

A difficult decision

The morning after, we had to make another decision, one that actually wouldn’t have existed. We exactly camped at that place where a steep, newly built gravel road was leading up the mountain next to us. A few days before, Andrew already warned us about this section of the road, as it is a super steep stretch with a really bad road. The original old road actually ran all along the river and Andrew suggested taking this one if it is still possible to go that way. At the junction of these two roads, just a few hundred meters next to our camp, we asked a local if we could take the old route. His answer was clear “No, no way”.

Nevertheless, we didn’t want to hear and once again, we decided in favor of adventure. In the end, it was exactly what we were here for, wasn’t it? For adventures that we can remember for the rest of our lives!

Let’s put it this way, we got what we were looking for and what we deserved.

Just about 2 kilometers down the old road, we arrived at the riverbank. Suddenly there was no longer a road, approximately 100-200m of the old road was underwater. A bit further, at a narrowness of the rocks, where only large boulders were left, there was a river coming down into the reservoir. After a long back and forth we dared to go for the “mini” adventure.

In order to somehow get to the other end of the old street, we first had to get our bikes and bags over these boulders and down to the river. After that, we had to carry them through the 10m wide river and finally, somehow bringing them to the main road, as there was only a steep wall and no footpath.

The first part was the easiest one, we had to carry bikes and bags separately along an earthy and slippery wall, approximately 50 meters, where we then had to give the equipment to two of our team, waiting to take them down to the riverfront. There, Favio and Andres were walking through the river, taking one peace by the other over the river. Viktor was already on the other side of the river, he was about to build a footpath into the steep wall. Luckily Viktor is an experienced rock climber who had his climbing ax with him.

Suddenly we heard a loud scream from Kata, who received the luggage on the other side of the river. The poles of their tent have fallen into the water and Andres so as Favio, with full commitment, trying to find them again in the murky river. I, standing on the other side of the river, wasn’t sure whether to be horrified or to laugh about that situation. Luckily they found the poles pretty quickly.

When we and all our luggage were on the other side, Viktor presented us with his self-made footpath. He made several steps into the wall which was about 5m high going straight down into the water. As an experienced climber, he took all the bikes through the wall on his own. Two of us were bringing the bags to the middle of the path to give them to the others for the second part.

Somehow we made it to the other side, from now on there was no way back and we still didn’t know how the “road” was looking like after the next corner. On the other side, we first made a break during the burning afternoon sun, unfortunately, we didn’t have that much water left. As we then cycled around 200 meters around the corner, we realized that this mini-adventure was not over yet. There wasn’t actually a road anymore, a stretch of about 2 kilometers was just covered with huge rocks and landslides. We spent the next hours carrying bikes and bags separately all up along this old road, or what was left of it. It was grueling!

After a total of 6 hours, we covered a stretch of 4.5 kilometers and finally arrived at the junction to the new road again. Though we almost lost a full day, we could laugh about ourselves, had an extra mini-adventure we won’t forget for a lifetime, and the certainty, that there is nothing in the whole Pamirs we can’t cross from now.

In the following picture, you can see our camp spot (yellow cross) so as the old road (red line). In the second picture, you can see the first part (yellow line), the river crossing (blue line), the wall (green line) so as the disappearing road full of landslides leading up to the new road.

Sadly I don’t have any pictures from the crossing itself, but fortunately, Viktor made a Video of it.

The Bataham Pass

In the next 3 days, we climbed through beautiful valleys on harsh gravel roads as it was expected. We found some more amazing camp spots just along the road or camped next to / or on one of the many volleyball fields you could find in almost every tiny village next to the school. Here we cycled and climbed the main part of the north road to Khalai-Khumb. The third day however was the hardest one. For the first time, we climbed up to over 3000m asl, from 1800m up to 3252m and the top of the Bataham Pass. The difficult part here was not the inclination but more the road condition. In many parts, it was almost impossible to keep cycling and we had to push again.

As we arrived at the top around 4 pm, we knew that it was not going to be a nice and smooth downhill to Khalai-Khumb from now. The road at the descent was as bad or even worse as when cycling up. We were constantly pulling our brakes, killing our brake-pads and finishing the day with a quite interesting last few hours cycling through the dark night.

River Panj, along the border with Afghanistan

In the small village of Khalai-Khumb, we stayed in a homestay to have a day off from the tough last days. Here we also found a well-stocked market again to prepare for the next days, and we also had time to check our bikes again, respectively changing the brake pads.

With Khalai-Khumb we also arrived at the Panj River, the edge of the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region (GBAO). The next few days we cycled on the left side along this river, which also forms the border to Afghanistan.

It felt interesting and special at the same time, looking to the other side of the river, seeing daily life in Afghanistan, men walking with heavily loaded donkeys, kids playing at the river bench, everything seemed peaceful, in a country which is affected by war for years. The views and nature looked as spectacular on the right as on the left side, afghan kids were shouting and happily waving at us, me thinking about the future of this beautiful country, hoping only for the best for its people.

This stretch cycling the Pamir Highway along the Panj river was quite busy with a lot of cars and trucks coming from both sides. Also the road here, in my opinion, was the worst so far. As on the northern route, it was more hard but loose gravel, here along the Panj it was hard but compact gravel from all the trucks, which made it even more bumpy and uncomfortable on long days in the saddle. Even though, the views still compensated for all that a hundred times.

Rushan

Finally, after 3 days cycling the Pamir Highway along the Panj river and the Afghan border, we arrived in the lovely small city of Rushan. Because we were already at 2000+ meters again, autumn was in full progress here. The fields and trees glowed in all different colors. This open valley around Rushan was nothing but incredibly beautiful. In Rushan, for the time being, the M41 came to an end for us, as it was also the place where we had to leave the Pamir Highway and head out for the wilderness and the Bartang valley.

How our adventures in the Bartang valley looked like, you’ll read in the second and last part about cycling the Pamir Highway and Tajikistan.

See you on the roof of the world!

Fabian

Special thanks to all of you for being part of my journey:

Favio, Andrew, Kata, Andres, Viktor

Pamir Highway FAQ

How high is the Pamir Highway

The majority of the Pamir Highway runs at an average altitude of about 2800-3000 meters asl. with its highest point at 4655 meters at the Ak Baital Pass.

Best time to visit the Pamir Highway

The best time to visit Tajikistan and the Pamir Highway is around May until September. While visiting the Pamir Highway in late autumn or winter is more challenging definitely a great adventure too.

Is the Pamir Highway paved

The majority of the Pamir Highway, also called the M41 is paved, altough there are a lot of potholes. There are some rough hard gravel sections, mainly along the panj river.

How long is the Pamir Highway

The Pamir Highway is around 1250km's long, from Dushanbe (capital of Tajikistan) to Osh in Kyrgyzstan.

5 comments

Absoltely marvelous! I’ve been looking forward to this post for a while. Rather amusing about the old road which no longer exists! But it will be memorable, for all the right reasons – a new challenge overcome! Looking forward to othe next parts!

Amazing! A Silk Road trip was in my plans for next year but now, who knows. I really enjoyed reading about yours. I just sent you an email about a project I’m working on to collect and share bike travel blogs. I would love to have yours be part of it!

Extremely inspiring… congratulation on this crazy adventur!

Hi Bastien

Happy you liked the read and thanks a lot for looking by!

Love this blog.

We are planning for June 2024.

Just wondering what type of bike you would recommend? I have a Vivente steel framed and designed for world travel but it doesn’t have suspension 🤔